Personal Goodwill: Can We Limit the Subjectivity?

Tony Garvy, ASA and James Arogeti, CFA recently co-authored the article, “Personal Goodwill: Can We Limit the Subjectivity” in the DuPage County Brief Magazine (February 2021):

“[G]oodwill is the value of a business or practice that exceeds the combined value of the physical assets.” 1 This definition stated in Marriage of Talty2 seems so simple, yet it opens the door to much interpretation and debate. The debate focuses on the allocation of the goodwill that separates what can be non-marital assets from marital assets, and thus, what can be valued and divided between divorcing parties. A recent unpublished Appellate Court opinion, In re Marriage of Preston, 3 demonstrates the types of issues the courts continue to wrestle with in dealing with this allocation of the Goodwill. In Preston, the court dealt with dueling experts with different methodologies for allocating the Goodwill of a company between Personal Goodwill and Enterprise Goodwill; one using the Multi-Attribute Utility Model (“MUM”) approach and one using the “with-and-without method.”4 Herein, we present the legal background for the allocation of Goodwill and methodologies for its allocation.

Illinois courts have recognized that Personal Goodwill is a non-marital asset and not divisible as marital property. The opinion from Marriage of Zells recognized a professional’s Goodwill is inseparable from that professional’s income potential, and thus Personal Goodwill is accounted for in maintenance. The court stated, “[i]f goodwill is that aspect of a business which maintains the clientele, then the goodwill in a professional business is the skill, the expertise, and the reputation of the professional… To figure goodwill in both facets of the practice would be to double count and reach an erroneous valuation.”5 The Zells court recognized the existence of Personal Goodwill in professional practices is not divisible as marital property as it is not realizable, and it would essentially be to “double dip” when also awarding maintenance. However, in the Marriage of Talty6 , the court recognized Personal Goodwill can exist in a non-professional business, such as an automobile dealership, where not all of the goodwill associated with the automobile dealership is personal to the owner, and some of the goodwill is likely valuable and could be valued as Enterprise Goodwill. Furthermore, in the Marriage of Schneider7 , the court determined that Personal Goodwill is a marital asset when the parties waive maintenance and found that it should have been included in the valuation of the husband’s dental practice.

By 2006, the courts expressed concerns regarding how appraisers determined Personal and Enterprise Goodwill. In Marriage of Alexander8, when valuing a medical practice, the expert adopted a model to remove some of the subjectivity from the process of separating Personal and Enterprise Goodwill. Prior to Marriage of Alexander, Illinois courts relied on subjective reasoning in determining Personal Goodwill. Marriage of Alexander introduced MUM, which allows appraisers to demonstrate reasoning behind their allocation between Personal and Enterprise Goodwill Factors.9 While MUM was one of the models proffered in Preston, it was criticized by the opposing expert for being too subjective.10

1. In re Marriage of Talty, 166 Ill. 2d 232, 238, 652 N.E. 2d 330, 209 Ill. Dec 790 (1995).

2. Id.

3. In re Marriage of Preston, 2018 IL App (2d) 170656-U, ¶ 25, 28 (August 1, 2018).

4. Id.

5. In re Marriage of Zells, 143 Ill. 2d 251, 255-56, 572 N.E. 2d 944, 946 (1991)(citation omitted).

6. In re Marriage of Talty, 252 Ill.App.3d 80, 85, 623 N.E.2d 1041, 1045-46(2nd Dist, 1993).

7. In re Marriage of Schneider, 214 Ill. 2d 152, 167, 824 N.E.2d 177, 824 N.E.2d 177, 186 (2005).

8. In re Marriage of Alexander, 368 Ill. App.3d 192, 195, 857 N.E.2d 766, 768 (5th Dist. 2006).

9. In re Marriage of Alexander, 368 Ill.App.3d at 198-200, 857 N.E.2d at 771-74.

10. In re Marriage of Preston, 2018 IL App (2d) 170656-U, ¶ 25, 31 (August 1, 2018)

Below we articulate two models that demonstrate ways of determining the allocation between Personal Goodwill and Enterprise Goodwill through perceptively less subjective inputs. Because Goodwill is a catch-all asset, it is our opinion that identifiable intangible assets can be identified, valued, and classified as Personal or Enterprise Assets. The following two types of analyses, Top-Down Analysis and Bottoms-Up Analysis, are quantitative methods that started in valuations for financial reporting purposes but now are utilized to determine goodwill allocation within the Family Law context.

Top-Down Analysis

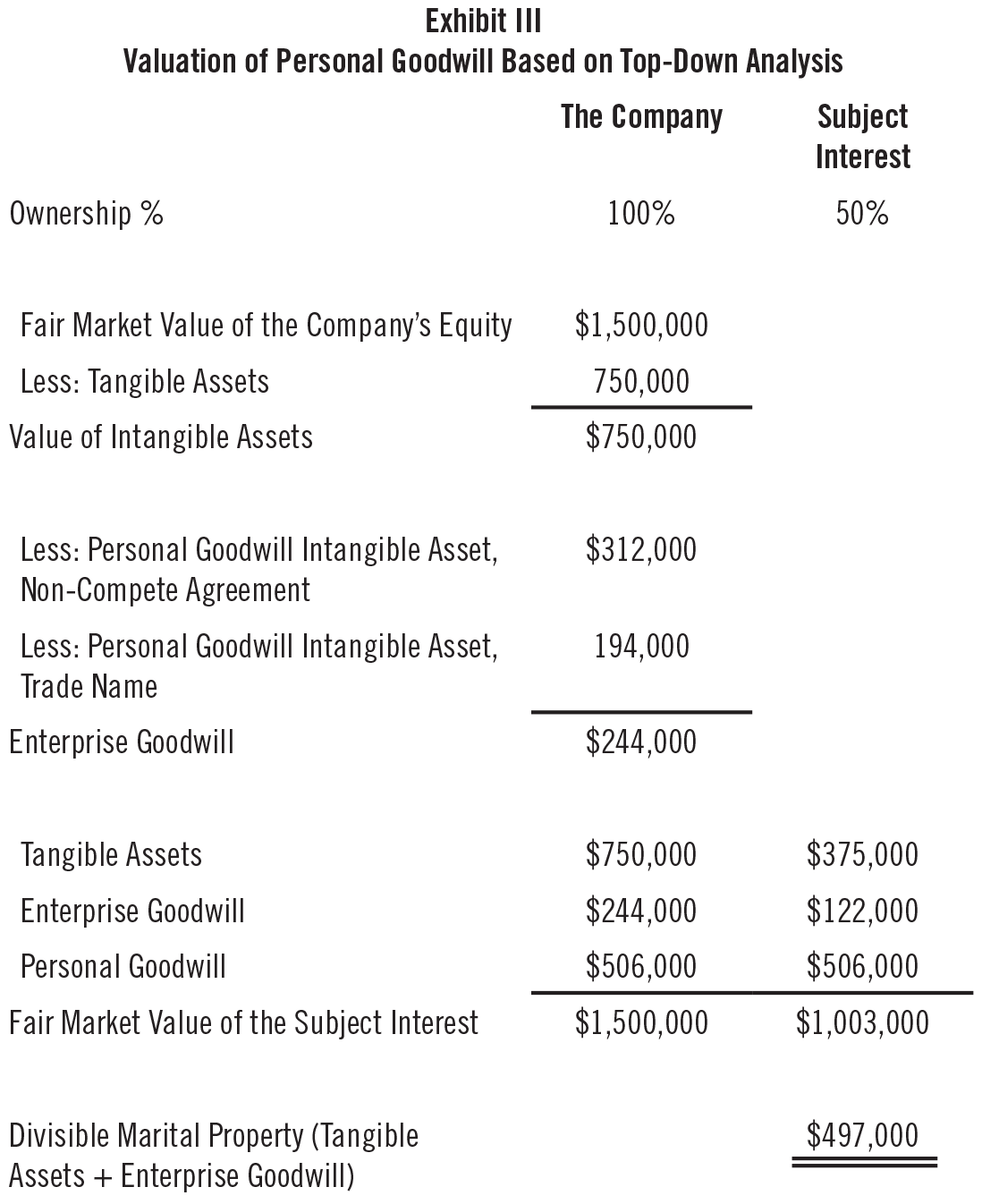

As the name suggests, appraisers start by determining the Fair Market Value of the company. Then, the appraiser identifies and values the intangible assets associated with Personal Goodwill: family name, owners’ reputation, employment contracts, etc. Finally, the value of identified intangible assets associated with Personal Goodwill is deducted from the company’s top-level value and the residual value is considered divisible within the marital property. For example: consider a home renovation company that specializes in restoring prairie-style homes with traditional materials and techniques (Wright Restoration). Wright Restoration is coowned by a brother/sister team. Mr. Wright recently entered into divorce proceedings and requires an appraisal of his 50% interest in the company. He has an active role in the company by handling the bid process and other day-to-day operations.

The sister has a smaller role in the company. The Company is named after their family and has a superior reputation in their community. The Company’s assets are appraised at $2,000,000 including $750,000 of tangible assets. The Company also has $500,000 of long-term debt. This yields $1,500,000 of total equity value.

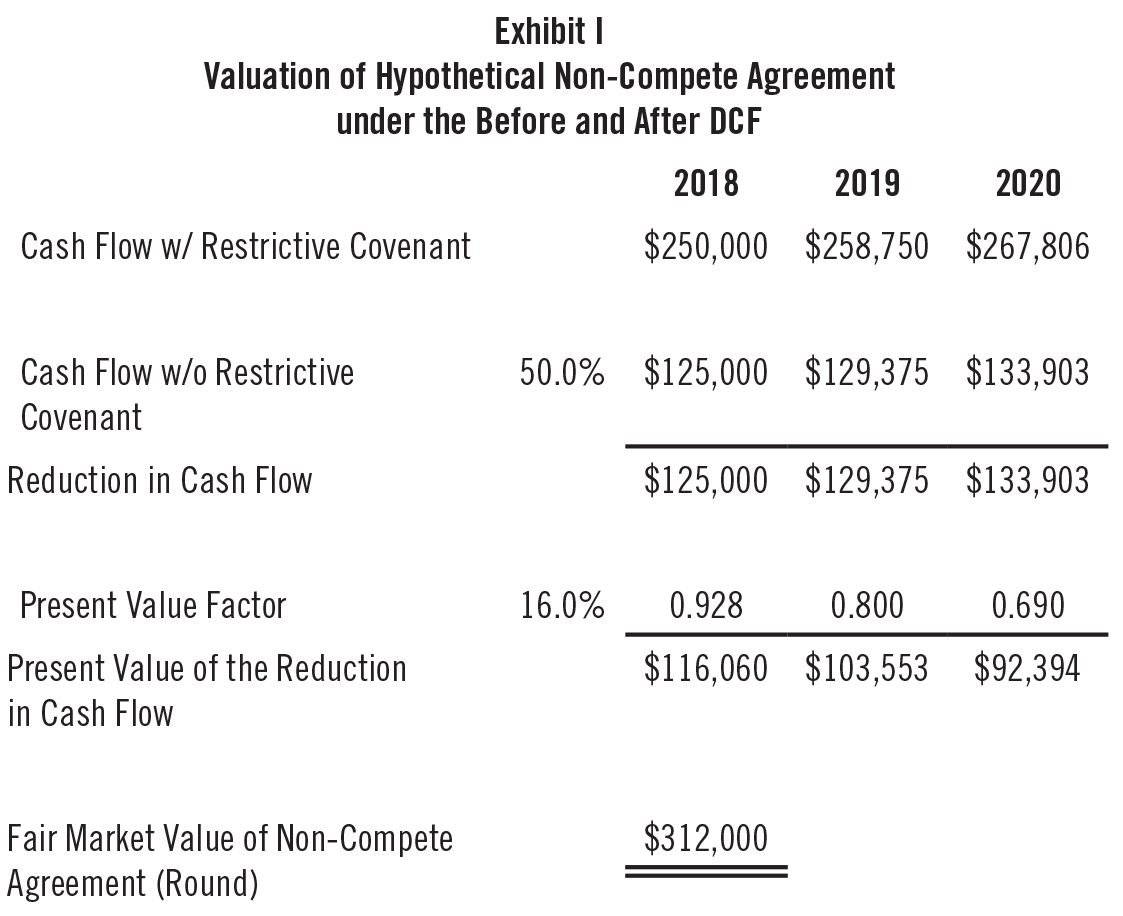

Of the $1.25 million of Goodwill value, we determined that it is partially made up of intangible assets classified as Personal Goodwill, and therefore not included in the marital property. We identified the hypothetical non-compete agreement and the company’s name as the Personal Goodwill intangible assets which are excluded from marital property. Although there was no non-competition agreement in existence, we assume the Willing Buyer would require a covenant to proceed with the hypothetical transaction. Therefore, we assert that the hypothetical non-compete agreement is Personal Goodwill because it hinders the Brother’s expected future income and thus would be a double dip into maintenance. We valued the non-compete agreement based on a Before and After Discounted Cash Flow analysis which falls under the Income Approach.11 We assumed that cash-flows would be reduced by about 50% for 3 years without a non-compete agreement. The resulting value of the non-compete is $312,000. (Exhibit I)

11. This analysis of Non-compete Agreements “before and after” is also called “with or without” analysis. This type of analysis was presented in Preston. In re Marriage of Preston, 2018 IL App (2d) 170656-U, ¶ 21.

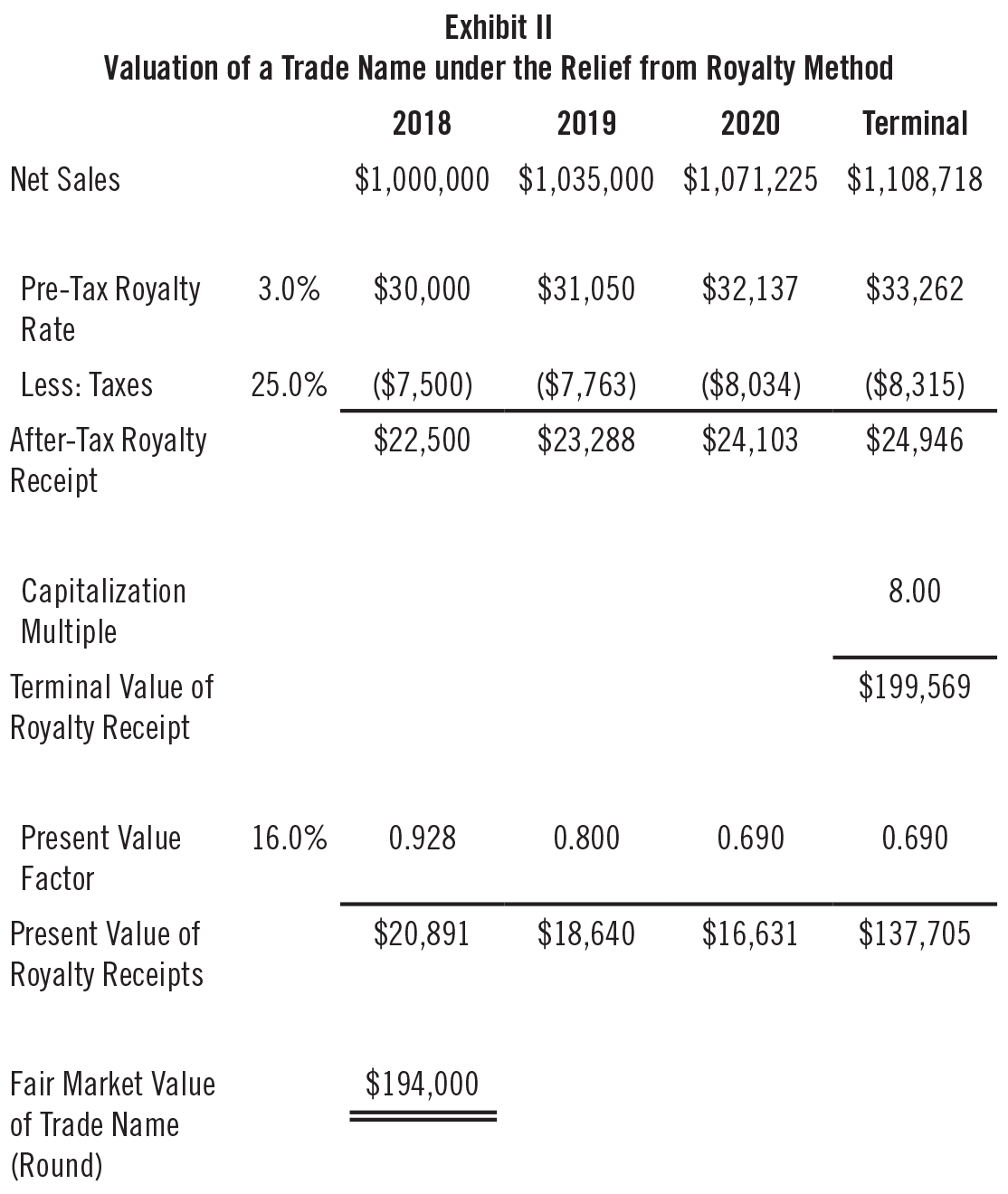

The company is named after the family and has a positive reputation within the community it serves. We utilized the Relief from Royalty Method under the Income Approach to value the trade name. Based on market data, we determined the royalty rate for a trade name in the industry is 3% of net sales. After accounting for taxes and the time value of money, we determined the fair market value of the trade name is $194,000. (Exhibit II)

Therefore, we can determine the value of the tangible assets and enterprise goodwill in arriving at the value of the Divisible Marital Assets. (Exhibit III)

"It is important to consider all three approaches presented in this article when faced with the challenge of appraising and allocating the goodwill of a company."

Bottom-Up Analysis

This approach is most often utilized when appraising intangible assets for financial reporting requirements, however, it is quite useful in the context of separating Personal and Enterprise Goodwill. This approach begins at the most basic level of valuation by appraising the company’s tangible assets. Next, the appraiser values the company’s Enterprise Intangible Assets. Any residual value is determined to be Personal Goodwill.

Identifiable Intangible Assets include: software, assembled workforce, trade names and marks, patents, non-compete agreements, customer relationships, etc. Based on the qualities of the underlying intangible assets, we would use the appropriate valuation methodology. For example, artistic and marketing-related Intangible Assets are typically valued by utilizing comparable royalty rates found in market datasets and determining the time value of licensing out the intangible. The Multiperiod Excess Earnings Method (“MPEE Method”) under the Income Approach is utilized for the intangible assets with the largest driver of revenue, typically customer relationships. This method values an asset based on its potential future earnings while taking into account the economic rent charged by the company’s other assets.

For example, take a temporary staffing agency with annual revenue of $5 million and a net profit margin of 5.5% after its third year of operation. We determined the business value of $2.36 million. The owner has 20 years of industry experience and a network of referrals. The firm has a manager/owner, a vice president of operations, three recruiters, three business development specialists, and one office staffer.

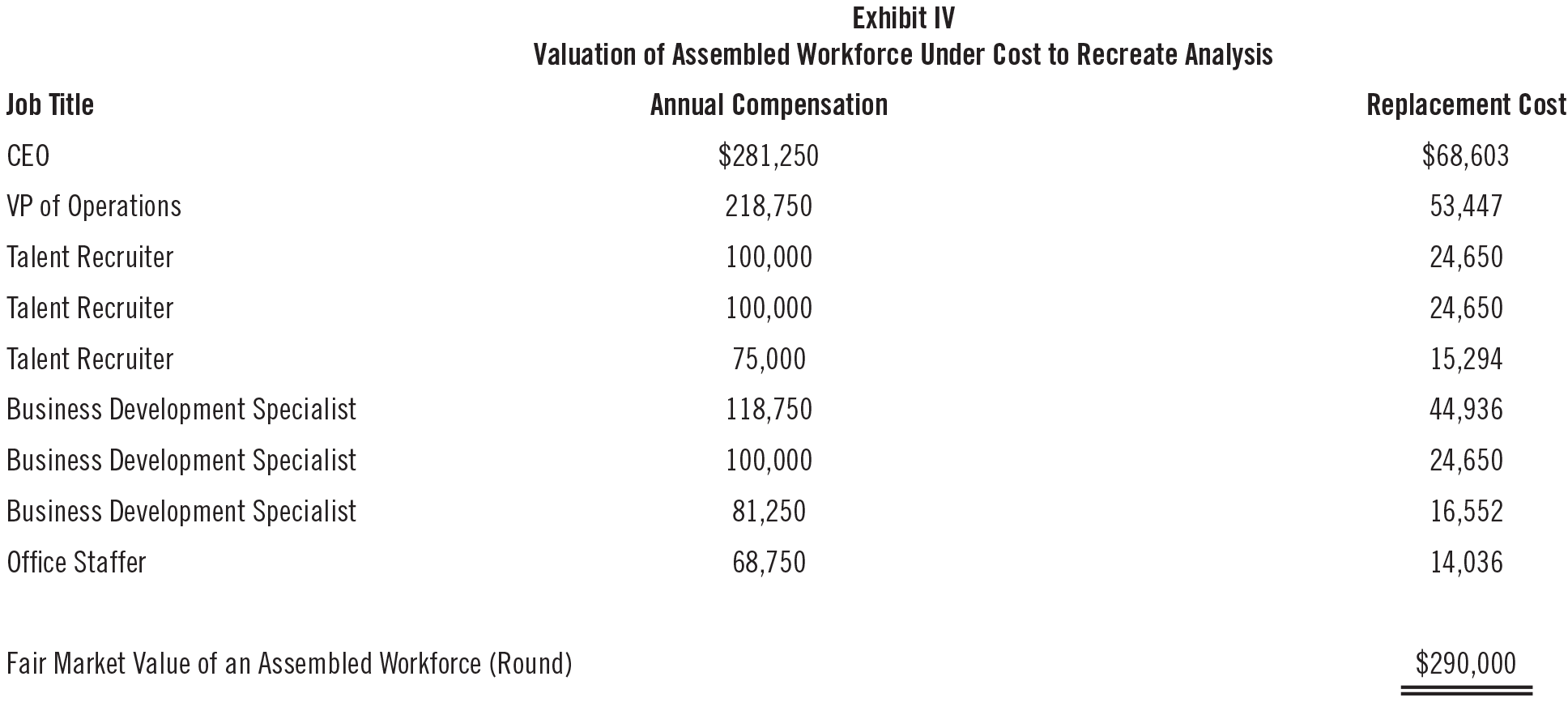

In determining the Personal Goodwill of the company, we identified and valued the Company’s Assembled Workforce and Customer Relationships as intangible assets. We valued the Company’s Assembled Workforce at $290,000 using the Cost to Recreate Analysis under the Asset Approach. We determined the replacement cost of each position based on cost of recruiting, hiring, and training a replacement employee for each position. (Exhibit IV)

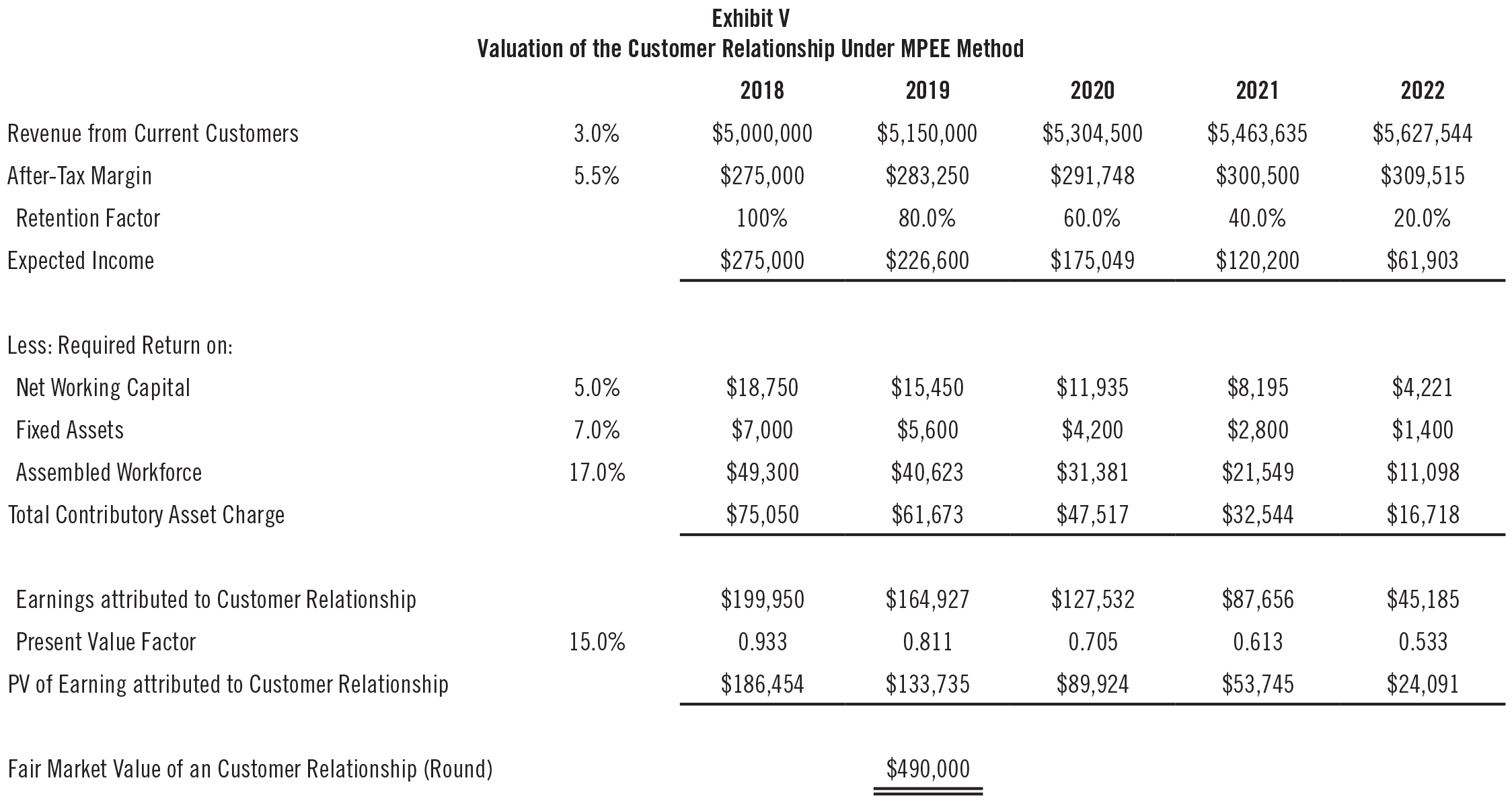

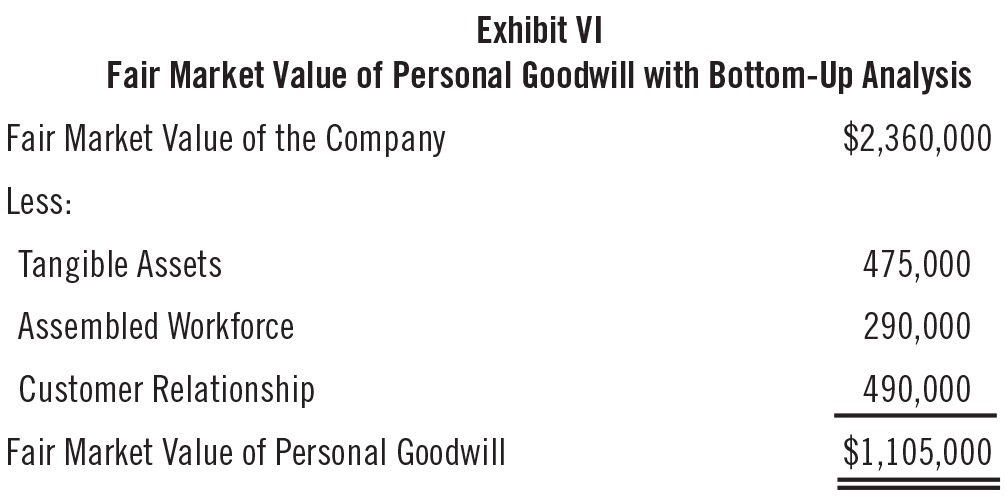

Next, we can determine the value of the Company’s Current Customer Relationships using the MPEE Method. We assumed a 3.0% long-term growth with straight-line deterioration of revenue attributed to the existing customer over five years. Then we subtracted the economic rent of 5.0% for net working capital, 7.0% for Fixed Assets, and 17.0% for the Assembled Work Force. Finally, we summed the Present Value of Earnings attributable to current customers to determine the Fair Market Value of the Customer Relationship of $490,000. (Exhibit V) After completing our analysis, the value of Personal Goodwill is determined by calculating the Company’s residual value by deducting its Tangible and Identifiable Intangible Asset. (Exhibit VI)

Drawbacks

It is important to consider all three approaches presented in this article when faced with the challenge of appraising and allocating the goodwill of a company. The MUM factors analysis is the most common amongst the three approaches and is a subjective approach to allocating between Personal and Enterprise Goodwill. This approach uses certain attributes of a company which are unique to its existence and splits them between personal and enterprise, then a weight is added to the more pertinent attributes.

Top-Down Analysis begins by appraising the entire company. After arriving at the top line value, Personal Goodwill is deducted, and the residual is part of the marital property. Bottom-Up Analysis begins with tangible assets and is added to Enterprise Goodwill to make up the marital asset.

Both Top-Down and Bottom-Up analyses provide a less subjective solution to allocating Personal and Professional Goodwill than Subjective Allocation or MUM Factor analysis. However, they have their drawbacks. They are more analytically complicated and are harder to explain to triers-of-facts than the subjective models like the MUM Factors. Also, they require greater time and information to execute than the subjective models. Yet, they provide a handy solution to the issues surrounding subjectivity within the MUM Factor Model.